Let's Learn About More Efficient State Management with FSM and Golang

Too Many States!

When working in the industry, you begin to notice that there’s a state for even the smallest details.

For example, there are states like user login status, order status, payment status, etc.

These states are usually stored and managed in code or a database and are used to perform different logic based on the state.

Prerequisite

The data handled in REST is also related to state as it stands for Representational State Transfer, but this article will deal with a more narrow definition of state.

Assume we have the following JSON record:

{

"name": "John",

"age": 30,

"state": "active"

}In REST, the entire record would be considered a state, but in this article, we will consider specific fields like state as the state.

Of course, in FSMs, the entire record can also be regarded as a state, but it’s not suitable for cases where many state branches would arise.

Problem

Typically, when managing state, an if-else or switch-case statement is used to implement different logic based on the state.

However, the more states you have, the more complex the code becomes, making maintenance difficult.

Given my experience managing the states of various resources on different shopping platforms like products, orders, and claims, I pondered a lot about converting the state of a product to the current service’s state.

Inevitably, writing the product’s state using simple if-else logic can lead to complex code, as shown below.

if product.State == "active" {

if product.Stock == 0 {

// Out of stock

product.State = "soldout"

}

if action.Type == "stop" {

// Stop sales

product.State = "stop"

}

if action.Type == "delete" {

// Delete product

product.State = "deleted"

}

} else if product.State == "soldout" {

if product.Stock > 0 {

// Stock refilled

product.State = "active"

}

} else if product.State == "stop" {

if action.Type == "resale" {

// Resell product

product.State = "active"

}

if action.Type == "delete" {

// Delete product

product.State = "deleted"

}

} else if product.State == "deleted" {

if action.Type == "restore" {

// Restore product

product.State = "stop"

}

} ...Though one might think it’s not a big deal due to the minimal internal code, if various logic needs to be performed based on the state, complexity would rise drastically.

Personally, I found it complex already with just this logic.

Having so many states plays a part too. The states embedded within the code must be recollected by the developer’s memory, which can lead to human errors like forgetting a ! in an if statement, or comparing the wrong state.

According to requirements, double or even triple nested if statements could be used to handle states, which again complicates the code and increases management costs.

FSM (Finite State Machine)

Now let’s learn about finite state machines (FSM) to manage states more efficiently.

FSM is about defining states and events and state transitions. It’s a concept widely used in game development but can be introduced to manage states when they are simply too many.

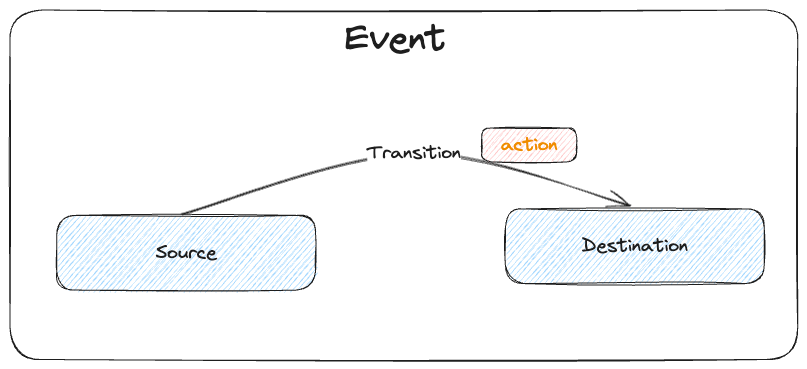

The general components are as follows:

- State: Define the states.

- Event: Define events that trigger state transitions.

- Transition: Define the state transitions.

- Action: Define the logic to perform during a state transition.

It’s a simple concept. You can view each Event collection as the FSM itself.

To understand this better, let’s express the previous if-statements as a diagram.

Each arrow’s start and end points represent states, and the arrows represent actions.

stateDiagram

Selling --> Out_of_stock: When the product is out of stock

Out_of_stock --> Selling: When stock is refilled

Selling --> Sale_suspension: When the seller suspends sales

Sale_suspension --> Selling: When the seller resumes sales

Selling --> Deletion: When the product is deleted

Sale_suspension --> Deletion: When the product is deleted

Deletion --> Sale_suspension: When the product is restoredDuring planning, you might receive such state diagrams. It’s easy to understand that converting this into code is what FSM is about.

FSM with Go

There are many state management libraries for implementation, but in this post, we will use the looplab/fsm library for our implementation.

Installation

go get github.com/looplab/fsmExample

Let’s implement the somewhat complex if-else statements we had earlier with FSM:

fsm := fsm.NewFSM(

"active", // Initial state

fsm.Events{

{Name: "detect-sold-out", Src: []string{"active"}, Dst: "soldout"},

{Name: "stop-sale", Src: []string{"active"}, Dst: "stop"},

{Name: "delete", Src: []string{"active", "stop"}, Dst: "deleted"},

{Name: "detect-stock-filled", Src: []string{"soldout"}, Dst: "active"},

{Name: "resale", Src: []string{"stop"}, Dst: "active"},

{Name: "restore", Src: []string{"deleted"}, Dst: "stop"},

},

fsm.Callbacks{

"detect-sold-out": func(ctx context.Context, e *fsm.Event) {

product, ok := e.Args[0].(Product)

if !ok {

e.Err = errors.New("invalid product")

return

}

// Don’t change to soldout if there is stock

if product.Stock > 0 {

e.Dst = e.Src

return

}

},

"detect-stock-filled": func(ctx context.Context, e *fsm.Event) {

product, ok := e.Args[0].(Product)

if !ok {

e.Err = errors.New("invalid product")

return

}

// Don’t change to active if there is no stock

if product.Stock == 0 {

e.Dst = e.Src

return

}

},

},

)The code would look as follows:

fsm.Events{

{Name: "detect-sold-out", Src: []string{"active"}, Dst: "soldout"},

{Name: "stop-sale", Src: []string{"active"}, Dst: "stop"},

{Name: "delete", Src: []string{"active", "stop"}, Dst: "deleted"},

{Name: "detect-stock-filled", Src: []string{"soldout"}, Dst: "active"},

{Name: "resale", Src: []string{"stop"}, Dst: "active"},

{Name: "restore", Src: []string{"deleted"}, Dst: "stop"},

},First, this part defines the events. Events like detect-sold-out, stop-sale, delete, etc., are defined, and state transitions for each event are defined.

This function automatically transitions the internal FSM state if its Src matches when fsm.Event(ctx, "{event_name}") function is called.

fsm.Callbacks{

"detect-sold-out": func(ctx context.Context, e *fsm.Event) {

product, ok := e.Args[0].(Product)

if !ok {

e.Err = errors.New("invalid product")

return

}

// Don’t change to soldout if there is stock

if product.Stock > 0 {

e.Dst = e.Src

return

}

},

"detect-stock-filled": func(ctx context.Context, e *fsm.Event) {

product, ok := e.Args[0].(Product)

if !ok {

e.Err = errors.New("invalid product")

return

}

// Don’t change to active if there is no stock

if product.Stock == 0 {

e.Dst = e.Src

return

}

},

},Callbacks define the logic to execute when each event is called. Events like resale, restore, etc., simply change states, so we handle them within FSM by changing the internal state and didn’t write separate callbacks.

However, for detect-sold-out and detect-stock-filled, since they reference the Stock field of the product resource separately, we decided to utilize additional arguments within FSM to use them.

e.Args allows passing arguments upon event calls in FSM, as fsm.Event(ctx, "{event_name}", product) is called, the callback function can refer to the product with e.Args[0].

Let’s test if it works as intended:

ctx := context.Background()

// When stock is 0 but the product is active

product := Product{

State: "active",

Stock: 0,

}

// Check stock and change the state

if err := fsm.Event(ctx, "detect-sold-out", product); err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

product.State = fsm.Current()

fmt.Printf("Product state: %s\n", product.State)

// Seller refills the stock to 10

product.Stock = 10

if err := fsm.Event(ctx, "detect-stock-filled", product); err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

product.State = fsm.Current()

fmt.Printf("Product state: %s\n", product.State)

// Seller stops the sale

if err := fsm.Event(ctx, "stop-sale"); err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

product.State = fsm.Current()

fmt.Printf("Product state: %s\n", product.State)

// Seller resumes the sale

if err := fsm.Event(ctx, "resale"); err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

product.State = fsm.Current()

fmt.Printf("Product state: %s\n", product.State)

// Seller deletes the product

if err := fsm.Event(ctx, "delete"); err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

product.State = fsm.Current()

fmt.Printf("Product state: %s\n", product.State)

// Seller restores the deleted product

if err := fsm.Event(ctx, "restore"); err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

product.State = fsm.Current()

fmt.Printf("Product state: %s\n", product.State)Running the above code will result in the following:

Product state: soldout

Product state: active

Product state: stop

Product state: active

Product state: deleted

Product state: stopAs shown, the state changes according to the action.

Visualization

FSM offers visualization capabilities. Not only this library, but many tools that pledge FSM support visualization through tools like Mermaid.

mermaid, err := fsm.VisualizeWithType(f, fsm.MERMAID)

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

fmt.Println(mermaid)You can visualize using the fsm.VisualizeWithType function as shown above, and it can be visualized in various forms such as mermaid or graphviz.

The output is as follows:

stateDiagram-v2

[*] --> stop

active --> deleted: delete

active --> soldout: detect-sold-out

active --> stop: stop-sale

deleted --> stop: restore

soldout --> active: detect-stock-filled

stop --> deleted: delete

stop --> active: resaleSince my blog supports mermaid, the visualization using this tool is as follows:

stateDiagram-v2

[*] --> stop

active --> deleted: delete

active --> soldout: detect-sold-out

active --> stop: stop-sale

deleted --> stop: restore

soldout --> active: detect-stock-filled

stop --> deleted: delete

stop --> active: resaleYou can see it allows quite a clean visualization.

Beyond this, various visualization methods are possible, and it might be possible to turn these into images and deploy them as links, allowing others to view state changes visually.

Conclusion

From a code perspective, FSM itself is not a tool that reduces code lines. In fact, the code might increase to accommodate FSM initialization and proper exception handling.

That doesn’t mean it looks bad; though the main function has everything here, in real-world scenarios, callbacks and events would be appropriately separated into modules, and the state and event definitions would be managed separately.

Nonetheless, the reason to use it is not to minimize code but rather to clearly define the state flow and relationships, making it easier to manage through visualization.

Through the clear Src and Dst definitions for state transitions and using callbacks to define actions, the code’s readability and maintainability are improved, reducing complexity even when numerous states are present.