(Github Actions) Executing with Github Runner when Self-Hosted Runner Fails

Recently, at our company, we transitioned from the Jenkins CI/CD we used to use to Github Actions, and began using the Self-Hosted Runner.

Self-Hosted Runner?

As the name suggests, a Self-Hosted Runner means a runner that is self-hosted. Instead of using a runner provided by Github when executing Github Actions, you use a machine that you have hosted yourself.

Since you are using your own computer directly, there can often be problems due to environmental constraints or cache issues, but it is faster and (excluding electricity costs) free to use compared to the Github Runner.

Why use a Self-Hosted Runner

The biggest issue with the current Jenkins setup was the time taken for tests. Although I refactored the existing code to reduce test time from 30 minutes to around 10 minutes — cutting it by a third — the introduction of Testcontainer for the increasing test code and repository tests unavoidably extended the execution time to 19 minutes.

The problem is that this test process is included not just when raising a PR, but also during deployment, prolonging the deployment time to around 30 minutes.

To solve this problem, we decided to use the Self-Hosted Runner.

It was good not only to use the company’s existing equipment but also AWS EC2 instances were being used in Jenkins. Self-Hosted Runners were much cheaper (electricity cost) compared to EC2 instances and had better performance. (Besides, setting them up is also easy.)

If the company does not have spare equipment, it would be a completely different story. Our company basically had spare machines that could be used as build runners, so we made this choice. In practice, comparing the cost of using high-spec runners provided by Github to purchasing computers should be prioritized.

While it’s possible to attach a Self-Hosted Runner to Jenkins, there were limitations like having to specify a fixed number of machines, so we chose Github Actions which could scale dynamically.

Issues

The issue is that the Self-Hosted Runner does not always function normally. Although this might also apply to the Github Runner, since these machines are managed directly by the company, occasions where the machines suddenly crash due to issues like aging network cables occasionally arise.

Each time that happens, checking and reviving a machine without knowing what’s wrong is quite a hassle.

If it’s an Organizational Runner, not just a project but all projects could be affected, leading to losses in wait time and downtime.

To solve such problems, we looked for a failover method to execute with a Github Runner when the Self-Hosted Runner is down.

Challenge

The problem is Github Actions does not officially provide a feature to execute with a Github Runner when a Self-Hosted Runner goes offline for some reason.

They support grouping multiple runner groups to execute simultaneously. However, since it’s simultaneous execution, if used extensively, you would end up paying for unused runners. (Especially as the default runners take a long time, the cost in terms of time could be expensive.)

Solution

Since it doesn’t exist, we had to find a makeshift solution. We structured the action based on an idea to check the runner’s state directly upfront and then route accordingly.

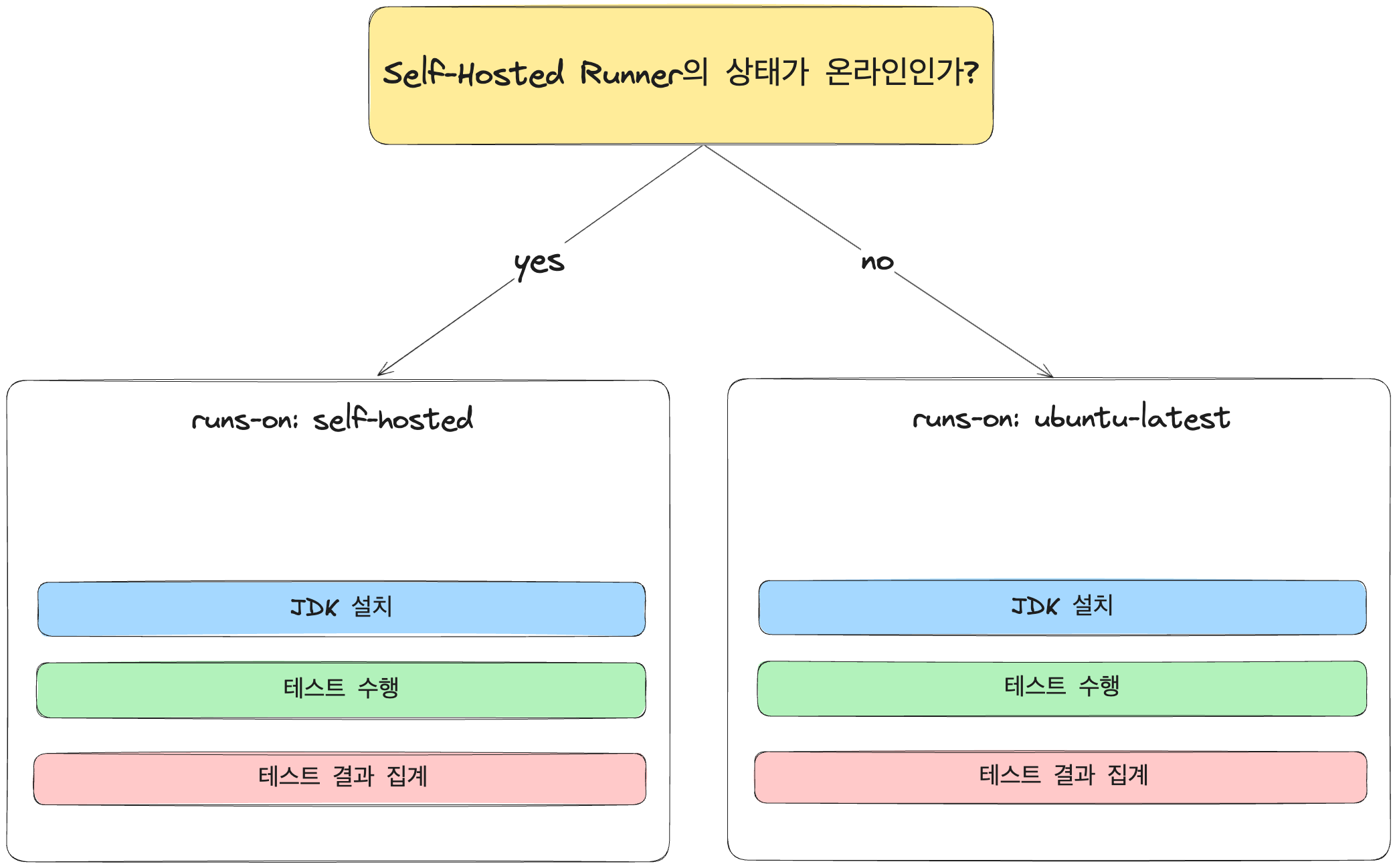

The flow can be outlined as follows:

ubuntu-latest refers to the Github Runner, and self-hosted refers to the Self-Hosted Runner.

The status check is structured to be based on runner information provided by the Github API.

The code looks like this:

name: Route Runner

on:

pull_request:

branches: [ '*' ]

jobs:

check_self_hosted:

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

outputs:

found: ${{ steps.check.outputs.found }}

steps:

- name: Is Self-Hosted Runner online?

id: check

uses: YangTaeyoung/self-hosted-runner-online-checker@v1.0.5

with:

runner-labels: 'self-hosted'

GITHUB_TOKEN: ${{ secrets.GH_TOKEN }}

call_self_hosted_runner:

name: Call self-hosted Runner for test

if: ${{ success() && needs.check_self_hosted.outputs.found == 'success' }}

needs: check_self_hosted

uses: ./.github/workflows/test-ci.yml

with:

runner: self-hosted

call_github_hosted_runner:

name: Call Github Runner for test

needs: check_self_hosted

if: ${{ success() && needs.check_self_hosted.outputs.found == 'failure'}}

uses: ./.github/workflows/test-ci.yml

with:

runner: ubuntu-latestEach test execution logic was made into a Reusable Workflow due to the lack of major differences between the Self-Hosted and Github Runner.

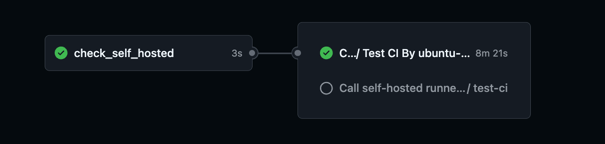

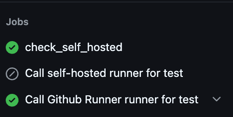

The first job titled check_self_hosted checks whether the Self-Hosted Runner is online and stores the result in found, the output of the job.

Then, in call_self_hosted_runner, if the Self-Hosted Runner is online, it executes tests with the Self-Hosted Runner, otherwise, it uses the Github Runner.

This way, if the Self-Hosted Runner is down, execution can proceed with the Github Runner.

Conclusion

Through this task, we explored a method to execute with the Github Runner when external incidents like natural disasters, aging network cables, or power failures leave the runner down.

Of course, errors unique to the runner are beyond our control, so the action is only structured to check for online status, but fundamentally, monitoring when a runner is alive and preparing responses for failure situations are necessary.

Despite these management costs, the overwhelming performance and cost-efficiency might be why one opts for a Self-Hosted Runner.